Oíche Fhéile Eoin – St. John’s Eve

Titeann Oíche Fhéile Eoin (‘St John’s Eve’) ar an 23 Meitheamh achan bhliain, an tráthnóna roimh ceiliúradh breithe Eoin Baiste.

Titeann Oíche Fhéile Eoin (‘St John’s Eve’) ar an 23 Meitheamh achan bhliain, an tráthnóna roimh ceiliúradh breithe Eoin Baiste.

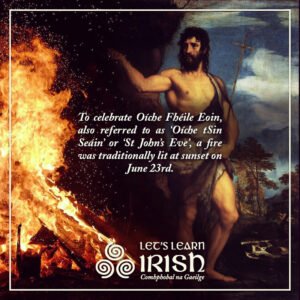

Oíche Fhéile Eoin takes place on June 23rd, on the eve of the Feast Day of St. John the Baptist. The festival is also referred to as ‘Oíche tSin Seáin’, or ‘St. John’s Eve’, and most likely originated in pagan times.

Clearly, Oíche Fhéile Eoin is a festival with its own unique origins and customs, and it’s closely associated with many Gaeltacht areas, but what’s it all about? Let’s sift through the cinders to find out a little bit more about this annual event…

What are the origins of Oíche Fhéile Eoin?

Scholars have noted the widespread tradition of bonfires throughout Europe, often marking the beginning and continuation of summer. Midsummer celebrations such as Oíche Fhéile Eoin echo the festival of Bealtaine on May 1st, with communities often worshipping the sun and calling for plentiful sunshine and good fortune towards their animals and crops. These midsummer celebrations have been observed in parts of Ireland for centuries, and have their roots in pre-Christian Ireland, when bonfires were lit in honour of the Celtic goddess, Áine. An equivalent of Aphrodite and Venus, Áine was the goddess of summer, wealth and sovereignty, and she is most associated with midsummer and the sun.

Scholars have noted the widespread tradition of bonfires throughout Europe, often marking the beginning and continuation of summer. Midsummer celebrations such as Oíche Fhéile Eoin echo the festival of Bealtaine on May 1st, with communities often worshipping the sun and calling for plentiful sunshine and good fortune towards their animals and crops. These midsummer celebrations have been observed in parts of Ireland for centuries, and have their roots in pre-Christian Ireland, when bonfires were lit in honour of the Celtic goddess, Áine. An equivalent of Aphrodite and Venus, Áine was the goddess of summer, wealth and sovereignty, and she is most associated with midsummer and the sun.

Most would agree that this pre-Christian festival was eventually co-opted by Christianity in honour of St. John the Baptist. The evolution of the festival towards a religious celebration in Ireland is likely due to the arrival of the Anglo-Normans, as there is little or no evidence of celebrations in honour of St. John the Baptist prior to the 1170s. This narrative aligns with what we know about similar midsummer bonfires in Europe, such as ‘Jāņi’ in Latvia (Jānis is Latvian for John) and ‘Sankthansaften’ in Norway.

Traditions of Oíche Fhéile Eoin

1. Bonfires

1. Bonfires

Traditionally, a fire was lit at sunset on June 23rd, and this bonfire continued to burn until long after midnight. Prayers were said in the hope of good crops and the avoidance of mid-summer flooding. Next, feasting, music, dance and fun would begin for young and old, including competitions of strength, agility and fire-jumping! It was also a tradition in some places for children to go around the village asking for “a penny for the bonfire” to buy sweets and cakes to eat that evening at the fire. Afterwards, it was customary for the cinders from the bonfires to be thrown on fields as an ‘offering’ to protect crops.

2. Feasting and Music:

Like many traditional festivals, Oíche Fhéile Eoin was also a time for feasting. Families and friends would gather to share food and drink, often around the bonfire. Traditional music and dancing would continue late into the night, reinforcing social bonds and community spirit. In some parts, a special dish called ‘Goody’ was served, consisting of white ‘shop-bread’ which had been soaked in hot milk and flavoured with sugar and spices. This food was prepared in a large pot on the communal bonfire, where locals would bring their own bowls and spoons. Older people drank poitín while younger folk would buy a barrel of beer or porter, to share all around.

3. Gathering Herbs and Flowers

3. Gathering Herbs and Flowers

In some parts, it was customary to collect flowers and herbs on Oíche Fhéile Eoin, as they were thought to be imbued with magical properties on this night. Particularly, the dew on these plants was considered potent for healing and protecting against harm. These herbs were often used to make wreaths which were then used to decorate the bonfire or worn by participants.

4. Fairy Forts and Holy Wells:

In some regions, people visited holy wells, believing the waters were especially blessed on this night. Rituals included circling the wells a certain number of times and leaving offerings. Likewise, fairy forts or ancient mounds were avoided or treated with respect due to beliefs about the aos sí (fairies) being particularly active during this time.

5. Divination:

The night was also a time for divination practices, particularly concerning marriage and prosperity. Young people would attempt various forms of fortune-telling to discover hints about their future spouses or predict the success of their agricultural endeavours.

Modern Celebrations

Today, Oíche Fhéile Eoin is still celebrated on June 23rd in many parts of Ireland. Some of the more ancient practices have waned in favour of modern festivities, which continue to emphasise community and enjoyment. Bonfires remain a popular tradition, around which communities gather to enjoy music, dance, and the warmth of shared celebration. Thankfully, the festival is a vibrant reminder of Ireland’s rich cultural tapestry, blending history, tradition, and community spirit. It serves not only as a cultural festivity but also as a link to Ireland’s ancient past, continually adapted by each generation to suit contemporary life while preserving connections to its roots.

Today, Oíche Fhéile Eoin is still celebrated on June 23rd in many parts of Ireland. Some of the more ancient practices have waned in favour of modern festivities, which continue to emphasise community and enjoyment. Bonfires remain a popular tradition, around which communities gather to enjoy music, dance, and the warmth of shared celebration. Thankfully, the festival is a vibrant reminder of Ireland’s rich cultural tapestry, blending history, tradition, and community spirit. It serves not only as a cultural festivity but also as a link to Ireland’s ancient past, continually adapted by each generation to suit contemporary life while preserving connections to its roots.

Join our upcoming term of 5-week Irish courses this summer – visit our Cúrsaí page for more details!

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.