Who was Pangur Bán?

There’s a joke out there that suggests that of all the ways we could use the once-unfathomable invention of the internet, there’s a notably non-proportionate number of cat videos out there. And however the joke is supposed to go, there’s truth behind the humor: people love their cats. Nonetheless, if there’s one thing to learn from the beloved poem “Pangur Bán,” it’s that people have loved their cats for a long time.

There’s a joke out there that suggests that of all the ways we could use the once-unfathomable invention of the internet, there’s a notably non-proportionate number of cat videos out there. And however the joke is supposed to go, there’s truth behind the humor: people love their cats. Nonetheless, if there’s one thing to learn from the beloved poem “Pangur Bán,” it’s that people have loved their cats for a long time.

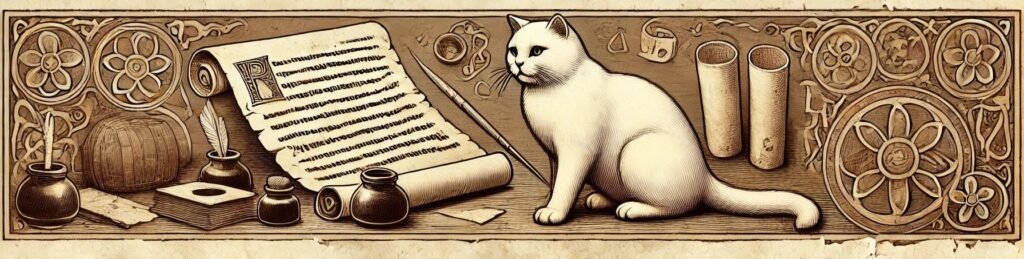

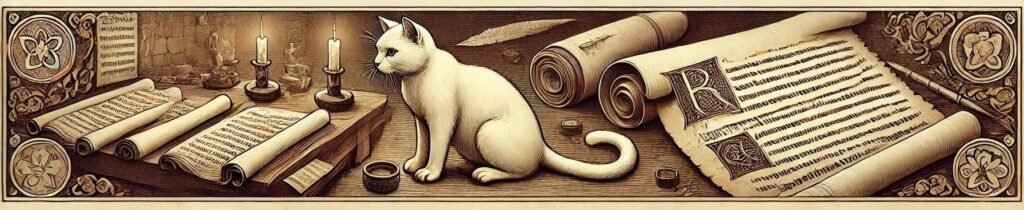

Written in the 9th century, the poem “Pangur Bán” is one of the oldest surviving texts from Early Ireland. Delivered in eight stanzas of four lines each, the verses explore the similarities of the author’s scholarly work to his cat’s pursuit of mice and how it brings them both pleasure. With bán meaning “white,” the name is still given to the occasional white feline in Ireland. (Pangur is thought to be a “fuller,” or someone who cleans the wool after it becomes fabric.)

Below is the poem “Pangur Bán,” with an English translation by Séamus Heaney, as well as a rendition of the poem by singer Pádraigín Ni Uallacháí and harp by Helen Davies.

Pangur Bán

Messe ocus Pangur Bán,

cechtar nathar fria saindán;

bíth a menma-sam fri seilgg,

mu menma céin im saincheirdd

Pangur Bán and I at work,

Adepts, equals, cat and clerk:

His whole instinct is to hunt,

Mine to free the meaning pent.

Caraim-se fos, ferr cach clú,

oc mu lebrán léir ingnu;

ní foirmtech frimm Pangur bán,

caraid cesin a maccdán.

Ó ru·biam — scél cen scís —

innar tegdais ar n-óendís,

táithiunn — díchríchide clius —

ní fris tarddam ar n-áthius.

Gnáth-húaraib ar gressaib gal

glenaid luch inna lín-sam;

os mé, du·fuit im lín chéin

dliged n-doraid cu n-dronchéill.

Fúachid-sem fri frega fál

a rosc anglése comlán;

fúachimm chéin fri fégi fis

mu rosc réil, cesu imdis,

Fáelid-sem cu n-déne dul

hi·n-glen luch inna gérchrub;

hi·tucu cheist n-doraid n-dil,

os mé chene am fáelid.

Cía beimmi amin nach ré,

ní·derban cách ar chéle.

Maith la cechtar nár a dán,

subaigthius a óenurán.

Hé fesin as choimsid dáu

in muid du·n-gní cach óenláu;

du thabairt doraid du glé

for mu mud céin am messe.

Who Wrote “Pangur Bán”?

The poem is anonymous. However, the style of the language used bears similarity to the work of the Irish monk Sedulius Scotus. His name meaning “sincere” or “diligent” Irishman, he taught in Liège, in what is now modern day Belgium. Born in Ireland, he was driven out by the Vikings and took refuge in Liège, where he became a scribe and poet. If “Pangur Bán” was written by Sedulius Scotus, given the difficult circumstances of his earlier life, it’s no wonder he can take pleasure in a quiet scholarly existence.

Where was the Poem Found?

“Pangur Bán” is written inside the Reichenau Primer, a manuscript containing eight folia and believed to have been composed in the 9th century. As per the name, it is assumed that the book was completed at the Abbey of Reichenau, a monastery founded on an island in the Rhine River in 724 AD and run by Benedictine monks. The Abbey of Reichenau was famous for producing ornate manuscripts.

Whether or not it was Sedulius Scotus who wrote “Pangur Bán,” the author is widely believed to be an Irishman, not just because the poem was written in Old Irish, but because the entire book was composed in insular script. A style created by Irish monks, insular script is characterized by large, decorative capital letters at the start of a paragraph, often with ornate adornment, and text that gets smaller in size towards the end of the page. In addition to “Pangur Bán” and several other poems in Old Irish, the Reichenau Primer contains Latin hymns, astronomical tables, Greek declensions, and brief notations in Old German.

The Significance of the Poem

It is widely accepted that “Pangur Bán” is the most famous surviving poem from Early Ireland. While much of its novelty largely derives from its age, having been written twelve centuries ago, part of its endurance in the modern imagination may be because of just how “un-novel” the poem is. A person’s close relationship to a pet is a theme that still resonates today, and one that can be found in many stories, movies and books. Perhaps one of the most intriguing aspects of “Pangur Bán” is that it shows us how much we still have in common with people who have lived over a millennium ago.

With its straightforward message, “Pangur Bán” has remained a favorite of school texts for Irish children, offering them a narrative that is easy to understand. However, because of its rich history and reverence in the Irish literary cannon, the poem has also attracted translations by famous poets in Ireland and abroad. Some notable writers who have translated the ancient text in addition to Seamus Heaney include Paul Muldoon, W. H. Auden, Robin Flower and Eavan Boland. Irish fiction laureate Colm Tóibín also wrote his own version of the poem, titled “Vinegar Hill.”

Twelve hundred years later, “Pangur Bán” still maintains a place in popular culture. For example, a cat named Pangur Bán appeared in the 2009 animated movie The Secret of Kells. As in the poem, Pangur Bán is a white cat belonging to a monk. Incidentally, the movie has caused some people to mistake the poem as being found in The Book of Kells, an Irish manuscript written about the same time as the Reichenau Primer. Nonetheless, the only surviving example of “Pangur Bán” is from the Reichenau Primer.

In the last couple of decades, the figure of Pangur Bán or the poem itself has been the bases for everything from children’s books (such as Jo Ellen Bogart and Sydney Smith’s The White Cat and the Monk) to a song by Dutch band (Twigs & Twine’s “Messe ocus Pangur Bán”). In 2018, Scottish singer Eddie Reader released a catchy song titled Pangur Bán and the Primrose Lass, and in 2022, an extinct mammal living 40,000 million years ago that resembled saber-tooth cats was named Pangurban.

Pangur Bán and Learning Irish Online

One of the many reasons people have for learning Irish is to connect to the heritage, culture and past of Ireland. There’s no better way to participate in the literary tradition of the island than to read its most revered works in its original language.

Although originally written in Old Irish, plenty of modern Irish versions of “Pangur Bán” exist. As such, the poem often finds its way into online Irish courses, especially advanced language classes. Studying a piece of literature from twelve hundred years ago in Irish offers a sense of just how old the language is, and the rich history behind it. The best way to pick up a language is to engage with it, and in reading “Pangur Bán” one can join centuries and centuries of Irish speakers who have done the same, being a part of a longstanding tradition.

Whether a cat person or not, it’s worth marveling at how a poem written so long ago can remain so relevant today. With many old texts in Irish focused on Irish mythology and other ancient stories, the domestic nature alone of one of Irish’s earliest surviving scripts makes it both intriguing and endearing. As evidenced by the “Pangur Bán” references in modern media, as well as the desire of many renown writers to approach the translation in their own way, it is clear the poem will continue to remain an important part of Ireland’s literary culture.

Join the online Irish community – beidh fáilte romhat!

Take a Course, join a Comhrá session or attend a Ceardlann.

For more, follow us @LetsLearnIrish – bígí páirteach!