Cló Gaelach: What is the Old Irish Script?

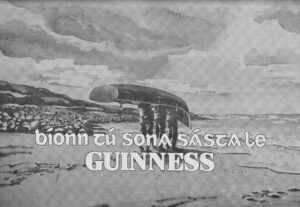

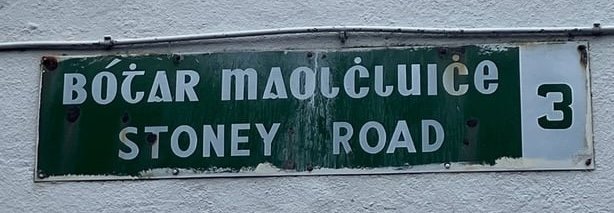

Are you familiar with Cló Gaelach or the term seanchló? The Gaelic script (or “old script”, as it was sometimes referred to) was the script traditionally used to write Irish. Cló Gaelach remains a valued part of Irish cultural heritage that is still occasionally used in signage, book titles, or formal inscriptions. The script continues to evoke a sense of history and tradition among speakers and learners of the language, but when did it begin and what’s its status now?

Are you familiar with Cló Gaelach or the term seanchló? The Gaelic script (or “old script”, as it was sometimes referred to) was the script traditionally used to write Irish. Cló Gaelach remains a valued part of Irish cultural heritage that is still occasionally used in signage, book titles, or formal inscriptions. The script continues to evoke a sense of history and tradition among speakers and learners of the language, but when did it begin and what’s its status now?

Cló Gaelach is believed to have been developed from the Latin alphabet and initially designed in the 16th century. Its first authentic version emerged in 1611 from the Irish Franciscans in Louvain. The script was most commonly used until the middle of the 18th century in Scotland and until the 20th century in Ireland.

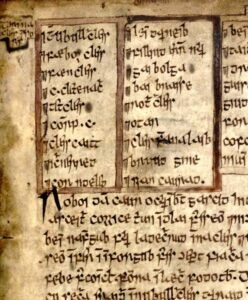

The Gaelic script was based on the style of penmanship used in the old manuscripts, such as the Book of the Dun Cow. The Book of the Dun Cow (Lebor na hUidre) is the oldest surviving manuscript written in the Irish language, dating from the 11th or early 12th century. Compiled by monks at the monastery of Clonmacnoise, it preserves a mix of mythological, religious, and historical texts. Most notably, it contains the earliest known version of the Táin Bó Cúailnge, the great epic of An Ruraíocht (the Ulster Cycle).

Although the youth of today remain largely unaware of it, there are hundreds of examples of Cló Gaelach to be seen on websites such as dúchas.ie and in any piece of Irish literature that was written before the middle of the 20th century. The Gaelic script was taught in schools throughout the country until the 1960s. Why was the use of the script discontinued and was this change justified?

Gaelic v. Latin Script

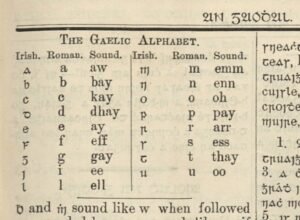

To begin with, what is the difference between the Latin (Roman) script and the Gaelic script? While both writing systems ultimately derive from the Roman alphabet, the Gaelic script developed distinct visual and functional characteristics over time, making it unique to the Irish language and its literary tradition.

One of the most noticeable features of the traditional Irish script is the use of the lenition dot, known in Irish as the ponc séimhithe. This dot is placed above certain consonants to indicate lenition, or séimhiú, a phonological process that softens the sound of a consonant. For example, the letter “b” with a dot over it (ḃ) is pronounced like a “v” sound in English. In the modern Latin alphabet used for Irish today, lenition is instead shown by inserting an “h” after the consonant, so ḃ becomes bh. The use of the ponc séimhithe was a distinctive and elegant feature of the old script, giving it a visual flair that is immediately recognisable to those familiar with traditional Irish writing.

One of the most noticeable features of the traditional Irish script is the use of the lenition dot, known in Irish as the ponc séimhithe. This dot is placed above certain consonants to indicate lenition, or séimhiú, a phonological process that softens the sound of a consonant. For example, the letter “b” with a dot over it (ḃ) is pronounced like a “v” sound in English. In the modern Latin alphabet used for Irish today, lenition is instead shown by inserting an “h” after the consonant, so ḃ becomes bh. The use of the ponc séimhithe was a distinctive and elegant feature of the old script, giving it a visual flair that is immediately recognisable to those familiar with traditional Irish writing.

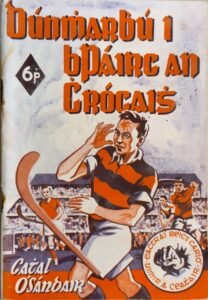

Another key difference lies in the shapes of the letters themselves. Several characters in the Gaelic script look quite different from their counterparts in modern Latin script. The letters “r” and “s,” for instance, can appear almost identical at first glance, often differentiated only by subtle curvature or stroke weight. This visual similarity can make reading older texts a challenge for the untrained eye. Similarly, the letters “g,” “d,” and “t” are written in stylised forms that deviate significantly from those used in contemporary English. The “g” in particular often has a more open and angular shape, while the “d” can have a long, ascender-like stroke that sets it apart – see examples of this and the ponc séimhithe in the cover of ‘Dúnmharbhú i bPáirc an Chrocaigh’ (pictured).

A particularly interesting feature of the Gaelic script is its use of the Tironian et (⁊), a shorthand symbol resembling the digit seven, used in place of the word agus, meaning “and.” This character has its roots in a system of Latin shorthand attributed to Marcus Tullius Tiro, a secretary of Cicero, and it was adopted into Irish writing where it remained in use for many centuries. The Tironian et is a striking example of how the Gaelic script preserved certain archaic traditions that had long disappeared from other European scripts.

In addition to these differences, the Gaelic script traditionally excluded several letters that are now part of the modern Irish alphabet, such as j, k, q, v, w, x, y, and z. These letters were not native to the Irish language and only appeared later with the introduction of English loanwords. Early Irish manuscripts, therefore, used a more limited character set that aligned closely with the phonology of Old and Middle Irish.

The aesthetic of the Gaelic script is also worth noting. Its rounded, flowing forms lend it an ornate and calligraphic quality, which was well-suited to the illuminated manuscripts produced by Irish monks in the early medieval period, such as the Book of Kells, the Book of Durrow and the aforementioned Book of the Dun Cow.

"Cranks" and A Change in Government Policy

When the 19th century came to an end in Ireland, Irish speakers appeared to be very much in favour of the Gaelic script. They wished to show strongly to those outside of Ireland that the people of Ireland had a unique language and culture. However, as time went on, people began to believe that there was no need for such a script.

While talking about the Gaelic script in the Comhdháil Náisiúnta na Gaeilge, the Irish politician Ernest Blythe referred to those who were in favour of the Gaelic script as “pedantic cranks“. He said they were an obstacle to the Irish movement and that they were even shaming the nation of Ireland. He looked at the script as though it were a remnant from the olden days and not at all modern or practical in use.

Interestingly, it can be argued that the Turkish Republic played a role in the change of Irish government policy towards the Gaelic script: in the year 1928, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk came to power in Turkey. One of his many projects was the alphabetical reform implemented in the country. The Arabic alphabet had been in use in Turkey up until that point, but an agenda of westernising reform and secularism was adapted with a view to aligning Turkey closer to mainstream Europe. From that point until the 1960s, the Irish Government changed their disposition towards the Gaelic script and steadily moved towards phasing it out in place of the Latin script. Blythe took inspiration from the Turkish example. The Gaelic script was viewed as archaic and out of step with modernity since there was no other version of the Latin alphabet used by other countries in Europe at the time. [See our article on the similarities between Irish and Turkish].

A Modern Application?

Although the official use of the Gaelic script is no more, you may still see it on pub signs and in old Irish books. As well as this, efforts do exist to revive use of the Gaelic script in this age of computers, such as Gaelchló; many different versions of the Gaelic script are available on their website. Some of the versions of the script they make are efforts to modernise the script while other versions look more traditional. The modern styles show us that the Gaelic script could still be used in a professional way today. You see the script represented in the Let’s Learn Irish logo, symbols and media too.

This all raises the question of whether we should cast aside this lovely script and completely adhere to the Official Standard now? I don’t think so. There is a certain beauty to the old script and whenever I write cards or letters in Irish, I always ensure to use cló Gaelach. Perhaps one could say that I am a “pedantic crank”, but it warms my heart when I see examples of cló Gaelach in a book or poster or hanging on a pub wall somewhere.

Of course, the difference between the Gaelic and Latin scripts is not just aesthetic – cló Gaelach reflects a linguistic journey of centuries and the cultural continuity in Ireland, as well as our unique literary legacy. I understand why so many Irish nationalists from the past century loved it too and why many people yearn for it now. Although I appreciate that it’s not necessary to teach the script in schools today, and that it may prove to be an obstacle for pupils, I still think it would be beneficial to acknowledge the script so that young people are at least aware of it. If that were to be done, maybe the pupils of today would better understand the rich history that the language possesses.

To learn more, see our recorded Ceardlann (Workshop) with Brian Breathnach, titled ‘An Cló Gaelach: Ón Stair go dtí an Lá Inniu’. Eolas anseo: LetsLearnIrish.com/courses/ceardlanna/

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.