Irish and Scottish Gaelic: Similar yet Different

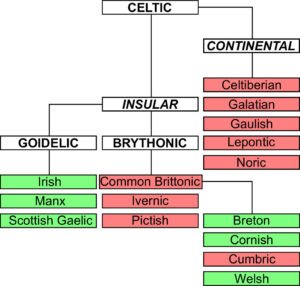

Irish and Scottish Gaelic are two of the six living Celtic languages, and both – along with Manx – form the “Goidelic,” or northern branch, of the Celtic language family. Both of their native names – Gaeilge and Gàidhlig – translate literally into English as “Gaelic.” Today, we generally reserve the term “Gaelic” for the Scottish language and simply use “Irish” to refer to the indigenous Irish Celtic tongue. However, it is technically correct to call Gaeilge as “Irish Gaelic.” Originally, both were one and the same language, brought to Scotland by Celtic tribes from Ireland, where it evolved into its own language by the thirteenth century.

Irish and Scottish Gaelic are two of the six living Celtic languages, and both – along with Manx – form the “Goidelic,” or northern branch, of the Celtic language family. Both of their native names – Gaeilge and Gàidhlig – translate literally into English as “Gaelic.” Today, we generally reserve the term “Gaelic” for the Scottish language and simply use “Irish” to refer to the indigenous Irish Celtic tongue. However, it is technically correct to call Gaeilge as “Irish Gaelic.” Originally, both were one and the same language, brought to Scotland by Celtic tribes from Ireland, where it evolved into its own language by the thirteenth century.

The two languages are similar enough that someone who can speak one of them comfortably may be able to comprehend the other, albeit with help from a dictionary at times. Irish and Scottish Gaelic sometimes draw comparisons to Spanish and Portuguese, which can be quite similar and share a high degree of mutual intelligibility in their written forms. A few Celticists even regard Irish and Gaelic as each being a distinct dialect (canúint in Irish; dual-chainnt in Gaelic) of what they see as the same language (teanga in Irish; cànan in Gaelic).

The two languages are similar enough that someone who can speak one of them comfortably may be able to comprehend the other, albeit with help from a dictionary at times. Irish and Scottish Gaelic sometimes draw comparisons to Spanish and Portuguese, which can be quite similar and share a high degree of mutual intelligibility in their written forms. A few Celticists even regard Irish and Gaelic as each being a distinct dialect (canúint in Irish; dual-chainnt in Gaelic) of what they see as the same language (teanga in Irish; cànan in Gaelic).

As one can see from the examples above, sometimes their vocabulary is recognisably similar. In other instances, terms can be dramatically different. Then again, what one would call a “lift” in Irish English is an “elevator” in American English, two dialects of what is clearly the same language.

However, looking at this from a different angle, I could express my fatigue to someone in Connemara by saying “Tá mé tuirseach.” But, if I were to go to the Hebrides and exclaim “Tha mi tùirseach,” someone would ring the local psychiatrist to get me an appointment for my depression! Note that the spelling of tuirseach is practically identical between Irish and Gaelic, save for the use of the grave accent mark over the “u” in the Gaelic spelling.

I often have people ask me which of the two is more difficult to learn. The jury’s still out on that one, at least for me, and perhaps that owes to the similarities between the two. For instance, someone studying Gaelic only needs to learn lenition, or the insertion of the letter ‘H’ after the initial consonant that occurs in certain situations. Known in Irish as the seimhiú, Irish learners not only have to learn that, but also the urú, or an additional consonant prefixed to the start of a word. While there are rules governing which an Irish speaker should use, sometimes there is no real rhyme or reason as to which one to implement. For instance, some Irish prepositions call for seimhiú for the word that follows while others use the urú. Even then, the dialect can influence this.

On the other hand, there is also the case system that gives English speakers migraines. Irish learners really only have to deal with the genitive case (check out this blog article for a short review on using it). However, Gaelic learners not only have to put up with the genitive, but also the dative case (here’s another blog entry on the Gaelic case system). To be clear, Irish does have the dative as well, although it has fallen into disuse, as I have learned in my recent coursework. Meanwhile, the Irish genitive remains alive and well.

Both Irish and Scottish Gaelic have their dialects, as nearly every living language does. In both, one will certainly meet pronunciation variations and sometimes spelling, vocabulary and usage differences. In Scottish Gaelic, one will find such distinctions, but they are not so glaring as to cause confusion. The most notable difference, to me at any rate, is between Scotland itself and the Gaelic diaspora in Nova Scotia, Canada. The latter has roundly rejected the spelling reforms made to Gaelic in the late 20th Century; one will still see the acute accent in use in words such as mòr [big], formerly spelled mór in Scotland and still spelled that way by some in Nova Scotia. In Ireland, the three dialects are diverse enough that they can seem like three separate but related languages in their own rights, particularly to someone who is just beginning their Irish journey. The textbooks teach one to greet a friend with “Conas atá tú,” but in Connemara, one never hears that textbook greeting. Instead, it’s “Cén chaoi a bhfuil tú?” In Ulster, it’s “Cad é mar atá tú?” Letslearnirish.com has a short blog and video post on this.

But why get stuck on grammar? Both Gàidhlig and Gaeilge have used the insular script – a variation on the Latin script strongly associated with Celtic languages and closely related to the uncial script – through the medieval periods. One will still find Irish written in that script on modern signage and especially on stonework such as tombstones. However, its use declined in Scotland and today is implemented when one wants to paint something with a Celtic flavour or (egad!) curry favour with the tourists. I wish Scottish Gaelic had kept the insular script; the photo of the memorial stone used here shows its artistic and aesthetic qualities versus the moderns scripts used to write languages now based on the Latin alphabet.

One thing that Irish and Gaelic share – and a reason I thoroughly enjoy learning and using them – is their beauty and expressiveness. Both are beautiful to speak and to hear. Both have musical qualities to them. One of my Gaelic instructors was fond of telling our class that one must practically sing in order to speak Gaelic. On a recent trip to Galway, I used some Irish with a hotel clerk, who praised me on having down the “musicality” of Irish in my speech cadence. I might not (yet) be fluent in Irish, but I took that as a high compliment on my progress. On a related note, I lived in Edinburgh for nearly two years whilst enrolled in the university there, and I often attended the Scottish capital’s only remaining Gaelic church services at the Greyfriars’ Kirk. Since it lies right in the middle of the touristy part of Edinburgh, visitors from abroad often attended. No, they did not have Gaelic and did not understand a word being said, but it struck me that they would frequently remark that hearing the poetic language spoken and sung made their hearts full.

Tha mi a’ creidsinn gu bheil Gàidhlig na h-Alba cànan ar cridhe. Táim cinnte go bhfuil Gaeilge teanga ár gcroí.

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.