Seamus Heaney and the Irish Language

Seamus Heaney, Ireland’s Nobel Laureate, was a poet who saw himself positioned on the borderline between identities. His father was a cattle-dealer and a farmer, while his mother’s side worked at the local linen mill. Heaney has always recognized this tension in his background, where his Gaelic agricultural past confronted the Ulster of the Industrial Revolution. Heaney stated that he internalized this tension—which was sometimes tangible between his parents—and it shaped his approach to looking at the world. This type of mediation between two cultures is useful when considering Seamus Heaney and the Irish Language.

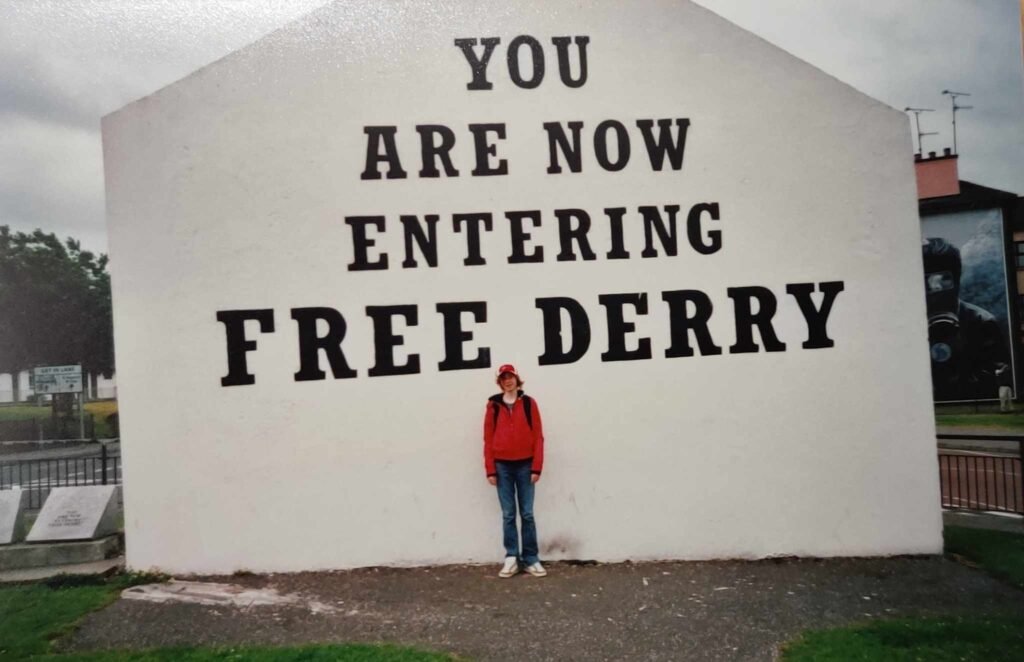

Seamus Heaney was born on a farm between Castledawson and Toomebridge in County Derry. Growing up in a border county, he lived among the political tensions between the two communities, coming of age only several decades after the Irish Civil War. As a result, he was well aware of the political tensions and history between the Irish and English language, both as a person and eventually as a poet.

In fact, some would argue that the heightened consciousness in using the Irish language is one of Heaney’s most defining traits as a writer.

The “Doubleness” of Heaney’s Poetry

Although all of the Seamus Heaney’s original poetry was written in English, it was often marked by the inclusion of Irish words. For example, his collection Wintering Out (1972) contains a poem titled “Maighdean Mara.” The poem is about a women who likely committed suicide by drowning herself. The Irish expression Maighdean Mara translations, roughly, as “Maiden of the Sea,” although Heaney leaves the term unexplained.

It has been argued that the merging of Irish words into his English language poems is reflective of Heaney’s identity as a poet from the north of Ireland, in a culture with both Irish and English influences. Some scholars suggest that it shows an awareness—perhaps even a privileging—of the Gaelic past, while operating in the dominant language of the island. This “doubleness,” some would say, represents the tensions of growing up in the North during a period of conflict.

Heaney as Translator from Irish

In addition to many volumes of original poetry, Seamus Heaney was also a prolific translator of works from other languages, including Irish. Human Chain, which would be his final collection, included translations of poems attributed to Colum Cille, an Irish abbot from the 6th century. He also gave his version of “Pangur Ban,” a 9th century poem by an Irish monk about his cat.

Seamus Heaney’s most famous translation from Irish, however, was Sweeney Astray, published in 1983 and winner of the 1985 PEN Translation Prize. Sweeney Astray is Heaney’s rendering of the Irish poem “Buile Shuibhne,” which was about Suibhne mac Colmáin, king of the Dál nAraidi, who was driven insane by the curse of Saint Rónán Finn. Heaney’s version uses the story to invoke contemporary feelings in a modern Ireland.

Ireland’s Nobel Laureate

In 1995, Seamus Heaney became Ireland’s fourth Nobel Laureate of Literature (following W.B. Yeats, George Bernard Shaw and Samuel Beckett). The committee stated that he was given the award “for works of lyrical beauty and ethical depth, which exalt everyday miracles and the living past.” The recognition cemented his legacy as one of the major poets of the 20th century.

Towards the end of his career, Heaney’s work enjoyed a level of popularity seldom experienced by a poet. In 2008, two-thirds of poetry collections sold in the United Kingdom were his titles. The next year he turned 70. Heaney marked the occasion by working with RTÉ, the national Irish media outlet, to record over 12 hours of his poems. This audio collection has become somewhat of a national treasure for Ireland.

Towards the end of his career, Heaney’s work enjoyed a level of popularity seldom experienced by a poet. In 2008, two-thirds of poetry collections sold in the United Kingdom were his titles. The next year he turned 70. Heaney marked the occasion by working with RTÉ, the national Irish media outlet, to record over 12 hours of his poems. This audio collection has become somewhat of a national treasure for Ireland.

Just as Heaney’s work cannot be considered without the context of where he was born, so, too, are Seamus Heaney and the Irish language connected. In addition to using it to masterful effect in his poetry, he was an advocate of taking up the language. As he said himself, “Not to learn Irish is to miss the opportunity of understanding what life in this country has meant and could mean in a better future. It is to cut oneself off from ways of being at home…”

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.