The Irish Origins of Hallowe’en

Dressing up, trick-or-treating, bonfires…Hallowe’en (Oíche Shamhna in Irish) is an unusual but beloved holiday. Because of its prevalence in the United States (although it is getting more popular in other countries), it is logically assumed that it is an American celebration. However, Hallowe’en – and many well known customs – trace back to Celtic Ireland and the festival of Samhain. While we see it as a fun reason to don a costume and allow children to overindulge in candy, back then the Irish people considered it necessary to their survival.

Going into Darkness

The Celtic religion was based on “the wheel of the year.” Bealtaine, on May 1st, was considered the start of the “lighter half” of the year, when the cattle were typically put out to pasture. Samhain, on November 1st (celebrations started on the eve of October 31st), marked the beginning of the “darker half” of the year. (Samhain is also the Irish word for “November.”) Livestock were brought in from the summer paddocks and the community braced for winter.

The Celtic religion was based on “the wheel of the year.” Bealtaine, on May 1st, was considered the start of the “lighter half” of the year, when the cattle were typically put out to pasture. Samhain, on November 1st (celebrations started on the eve of October 31st), marked the beginning of the “darker half” of the year. (Samhain is also the Irish word for “November.”) Livestock were brought in from the summer paddocks and the community braced for winter.

More importantly at Samhain, however, the boundaries between this world and the otherworld were at their thinnest. This allowed the spirits of the dead (Aos Sí) to pass through. Sometimes burial tombs were even opened under these expectations. With ancient life being precarious enough, the Celts didn’t want their crops or cattle to be affected by the spirits. Hoping to escape their wrath and survive the winter ahead, communities looked for ways to appease the Aos Sí.

The Start of Hallowe'en Traditions

In order to pay homage to the spirits that might cross over on Samhain, the Celtic people burned crops and livestock in bonfires as a sacrifice. As one of four Celtic “fire festivals,” the fire was meant to be an act of cleansing as the community prepared for winter. While not as common in the US, bonfires are still a tradition in Irish culture, and not only at Hallowe’en. The fires were meant to mimic the power of the sun and hold back the decay and deterioration associated with the darkness of the coming season. Some accounts suggest that the ashes from these fires had protective powers.

Another way to avoid the acrimony of dead spirits is to make sure that they can’t see you. The tradition of dressing up as scary, ghoulish creatures is thought to have come from the Pagan Irish disguising themselves as dead or evil spirits in order to not be noticed by the Aos Sí. At times, other precautions included wearing one’s clothes inside out or carrying salt with them. Others carried a parshall, which was a small cross made of sticks and straw that got replaced each Samhain. Many people didn’t stray far from their homes on Samhain, just to avoid any unfortunate encounters.

And how could we forget the practice of carving up jack-o-lanterns from pumpkins, which were traditionally made with turnips! However, while this was a practice taken up later in Irish history, it was still meant to ward off unsavory spirits, and the light inside had a similar significance as the earlier bonfires.

And how could we forget the practice of carving up jack-o-lanterns from pumpkins, which were traditionally made with turnips! However, while this was a practice taken up later in Irish history, it was still meant to ward off unsavory spirits, and the light inside had a similar significance as the earlier bonfires.

Come November 1st, the Celtic people’s dealings with the supernatural was not quite over. While hopefully most of the Aos Sí were content to return to the otherworld, communities still had to consider the púca. The púca (púcaí in the plural form) were spirits with a particular aptitude for mischievousness. Although they seldom did serious harm in the remote areas they were found in, they still liked to play tricks on passersby, such as taking the form of a horse and giving the unexpecting person a wild ride before leaving them back at the same place. Perhaps not unrelated, they sometimes did this to those who were inebriated, causing them to be late in coming home.

Much like the Celts did for the rest of the Aos Sí the night before, sometimes farmers left a portion of their crops in the field as “the púca’s share.” Because November 1st was considered the end of the harvest season, it was suggested that berries and fruits unpicked at that time spoiled because the púcaí had spit or defecated on them.

The Church Gets Involved

In 609 Pope Boniface IV created a holiday called All Saints Day, also known as All-Hallows. The evening before, not surprisingly, was called All-Hallows Eve (precursor to the term “Hallowe’en”). Originally in May, Pope Gregory III later moved All-Hallows to November 1st in order to capitalize on the popularity of the pagan festival Samhain. Honoring ghosts and saints were customs similar enough that the church thought it a better strategy than discouraging Samhain.

In 609 Pope Boniface IV created a holiday called All Saints Day, also known as All-Hallows. The evening before, not surprisingly, was called All-Hallows Eve (precursor to the term “Hallowe’en”). Originally in May, Pope Gregory III later moved All-Hallows to November 1st in order to capitalize on the popularity of the pagan festival Samhain. Honoring ghosts and saints were customs similar enough that the church thought it a better strategy than discouraging Samhain.

To celebrate the saints, it was still encouraged to light a bonfire and dress up as otherworldly spirits. Whereas the Celts offered food and drink to the Aos Sí, the church encouraged people to do the same for the poor. The tricks and pranks attributed to evil spirits were replaced by acts of generosity that was meant to manifest the spirit of the saints.

Hallowe'en in Ireland Today

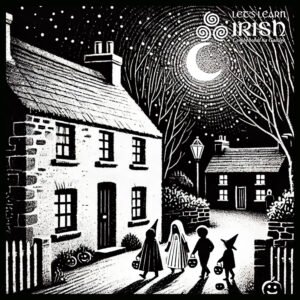

While many traditions remained throughout the centuries, All-Hallows Eve eventually became more celebrated than All Saints Day. Going door to door in costumes or giving a small performance in exchange for money or food became increasingly popular in the modern era.

Although trick-or-treating for candy has only recently become a practice in Ireland, the island where Hallowe’en started has come to embrace the holiday wholeheartedly. The city of Derry is often said to hold one of the best Hallowe’en festivals in Europe and attracts visitors from all over the world. Don’t be surprised if you spot folks dressed up as an chailleach at this time of year!

Although trick-or-treating for candy has only recently become a practice in Ireland, the island where Hallowe’en started has come to embrace the holiday wholeheartedly. The city of Derry is often said to hold one of the best Hallowe’en festivals in Europe and attracts visitors from all over the world. Don’t be surprised if you spot folks dressed up as an chailleach at this time of year!

If you’re in Ireland on Hallowe’en you can also enjoy the Púca Festival in County Meath. To commemorate the Samhain traditions of the Celts, a fire is lit on Tlachtga (Hill of Ward) in Athboy, the site of much ancient history in Ireland. In the nearby town of Trim, the festival has a “Gathering of the Spirits” parade, as well several nights of “music, comedy, fire and feasting.” It’s a great way to combine history and fun in honoring the ancient holiday.

An Original Way to Celebrate Hallowe'en

Considering the Irish origins of Hallowe’en and the rich culture of mythology and folklore behind the traditions, what better way to embrace the holiday than to learn some Irish? Oíche Shamhna is a fun topic to take up in conversation, and you can use words like reilig (graveyard), cnámharlach (skeleton) and puimcíní (pumpkins) in an amusing way. Describe the costumes and decorations you hung up in the same tongue that the original practitioners of Hallowe’en used. To help you get started, we’ve put together this video and handy list of Hallowe’en vocabulary.

In addition to the bags of candy, creative costumes, and neighborhood parties, you can take pleasure in knowing that you’re following in the footsteps of Celtic pagans from thousands of years ago. These fun activities were once thought of as acts of survival as communities tried to negotiate the otherworld. Samhain was a night when everyone was on edge to see what the spirits would do, likely providing the nervous energy of the Hallowe’en horror movies that would follow centuries later. This Hallowe’en, embrace that tradition by picking up a few words in Irish and watching out for the Aos Sí…

In addition to the bags of candy, creative costumes, and neighborhood parties, you can take pleasure in knowing that you’re following in the footsteps of Celtic pagans from thousands of years ago. These fun activities were once thought of as acts of survival as communities tried to negotiate the otherworld. Samhain was a night when everyone was on edge to see what the spirits would do, likely providing the nervous energy of the Hallowe’en horror movies that would follow centuries later. This Hallowe’en, embrace that tradition by picking up a few words in Irish and watching out for the Aos Sí…

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.