Comhfhocail – Compound Words

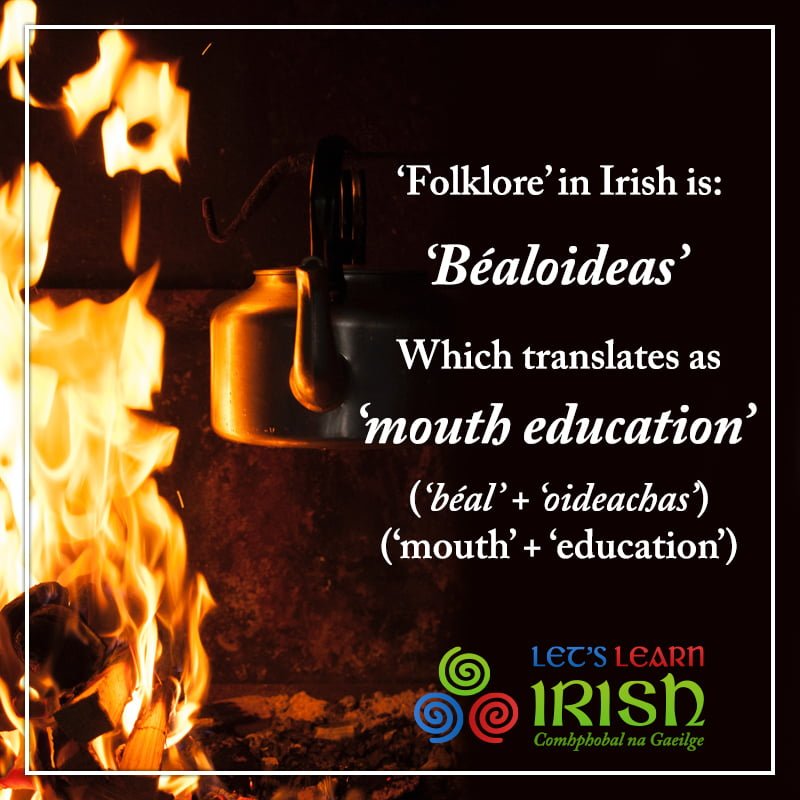

There is no denying that even up to recent times, the oral sharing of knowledge, both for education and entertainment, has been a landmark of the Irish tradition. Modern communication sciences have long demonstrated the capacity of myth, folklore and storytelling to carry solid bits of information across impossibly long and convoluted periods of time, and in a way, Ireland is rather unique in the survival of its ancient traditions.

A very characteristic landmark of the Irish language is its capacity for clever and endearing composition of new words based on other words. These are called ‘comhfhocal’, meaning “compounded word”. An example of itself, this word is actually a compound word: with ‘comh-’ (joint/jointed) and ‘focal’ meaning word. Comh-fhocal = Jointed-word.

A comhfhocal is a word which is made up of at least two parts – the main word itself and a prefix before it. The prefix can be a word in its own right (e.g. sean, meaning ‘old’, eg. seanbhean), or a true prefix, i.e. it’s not used as a word on its own (e.g. ‘mí’ (un/dis); ‘il’ (multi). Below are some examples of comhfhocail:

Ollmhargadh (supermarket)

Ollscoil (university)

Olltoghchán (general election)

Mícheart (wrong)

Míshásta (unhappy)

Míchompordach (uncomfortable)

Rómhór (too big)

Róbheag (too small)

Róchiúin (too quiet)

Príomhchathair (capital city)

Príomhtheanga (main language)

Príomhoide (headmaster, principal)

Seanathair (grandfather)

Seanmháthair (grandmother)

Seanfhear (an old man)

Drochlá (bad day)

Drochdhuine (a bad person)

Drochscéal (a bad story)

Fíormhaith (very good)

Fíorbhrón (very sorry)

Fíorbhuíoch (very grateful)

Ildaite (multicoloured)

Ilteangacha (multilingual)

Ilchreidmheach (multidenominational)

Athbhliain (new year)

Athchúrsáil (recycle)

Athdhéanamh (redo)

Indéanta (possible)

Infheicthe (visible)

Inite (edible)

Dodhéanta (impossible)

Dofheicthe (invisible)

Dobhriste (unbreakable)

Perhaps my favourite example of a comhfhocal is ‘béaloideas’, the Irish word for ‘folklore’. This word is composed of the Irish words for ‘mouth’ and ‘education’, something which highlights, much better than English, the importance (and capacity) of oral transmission to educate, inform and instruct. Interestingly, the word for ‘education’ itself, ‘oideas’, derives from an Old Irish word, ‘aites’, which means ‘foster parent’ but also “tutor, teacher”. Combined with the suffix ‘as’, which means ‘out of’, you get ‘oideas’ – something that “comes out of” your tutor: education!

Join the online Irish community for cúrsaí, comhrá & ceardlanna, and follow along on social media @LetsLearnIrish – beidh fáilte romhat!