Language Standardization in Irish: A Note on An Caighdeán Oifigiúil (the Official Standard)

An Caighdeán Oifigiúil (the Official Standard) is the Irish Government’s state sponsored guidance for writing in the Irish Language. First published in 1958, as a standard for “official business” and as “a guide for teachers and the public in general”, the Caighdeán has had a significant impact on Irish language writing over, almost, 70 years.

Below, I discuss, briefly, the development of the standard, its review within the last decade and its lasting influence on the Irish Language community.

Gaelic Revival and a new state

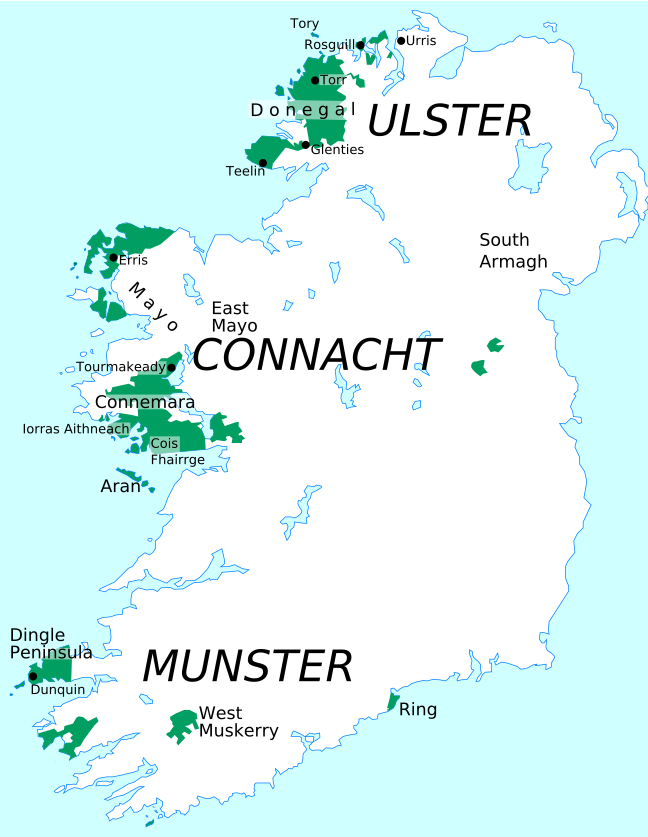

In the broadest sense, Irish has 3 major dialects that can generally be aligned with the provinces of Munster (M), Ulster (U) and Connacht (C). Each of the dialects have their own linguistic characteristics; sometimes these characteristics converge (i.e. they are the same or similar) and on other occasions they diverge (i.e. they are different from one another). This situation developed over time and can be seen in different components of the language; in vocabulary, in grammar and in phonology, for example.

By the early 20th Century, revivalists engaged in efforts to reestablish Gaeilge as a language of common usage in Ireland, were faced with this complex linguistic situation. The fostering of an Irish national identity was in bloom at the time, but so too was the dialectally diverse new literature of Caint na nDaoine, the type of writing in Modern Irish based on the speech of the people. It was cultivated with passion by a new generation of writers, including Peadar Ua Laoghaire, Padraig Mac Piaras, Pádraic Ó Conaire, Séamas Ó Grianna, Seosamh Mac Grianna and others.

When the turbulence of the revolutionary period began to ebb, a new state was founded; and the Irish Language was returned to the corridors of power and officialdom for the first time since the fall of the old Gaelic order. The new Irish Free State (1922) tasked Rannóg an Aistriúcháin (the Translation Department) with the elaboration of the language in new domains, like science, education, governance and law. In the succeeding decades, this involved the development of new terminology, the embedding of the roman font, a simplification of spelling and a standardization of grammar.

Language Standardization usually promotes the idea of uniformity and a minimization of variation. Considering the significant dialectal diversity of Irish, these moves towards standardization in the written language were not without their challenges. There were well known figures in the Irish Language community in favor of the developing government standard, but there was also criticism and opposition; particularly amongst those who viewed it as an imposition by the state at the expense of living Gaeltacht dialects.

An Caighdeán Oifigiúil and its Review

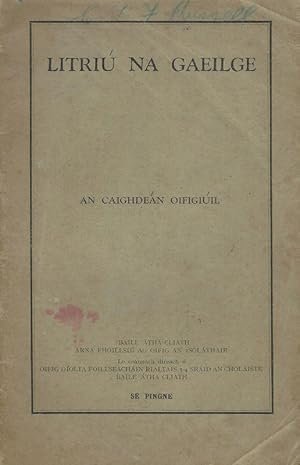

In 1945 Litriú na Gaeilge: an Caighdeán Oifigiúil was published embedding the standardized spelling system we use today. An Caighdeán Oifigiúil itself was published in 1958, laying out a prescriptive basis for the grammar of Irish. It was followed by other notable publications which contributed significantly to the standard language: de Bhaldraithe’s English-Irish Dictionary (1959), the Christian Brother’s Graiméar Gaeilge na mBráithre Críostaí (1960) and Foclóir Gaeilge-Béarla by Niall Ó Dónaill (1977).

Debate, and complaint, about the prescriptive conventions of the standard language as laid out in the Caighdeán Oifigiúil (1958), and in the publications forementioned, filled a void of around 50 years before the Official Standard grammar would be reviewed. Criticisms of the Caighdeán during that period included want of clarity, a lack of Gaeltacht-authenticity in particular rules and an uncertainty perpetuated by differences between the conventions of the Caighdeán and those recommended by the Christian Brothers and in the dictionaries.

A Standard for the future?

The conventions of an Caighdeán Oifigiúil have undoubtedly left their mark on writing in Irish. We can see their imprint on the language we use today in a wide range of areas, from literature to legislation. The implementation of the standard in our education system means that few, if any, Irish language users escape the implementation of standardized Irish. Arguably, from a learners’ perspective, standardization simplifies the learning process, allowing for a type of centralized target language.

Nonetheless, let’s remember that standard Irish is not a spoken dialect. It can perhaps best be described as an additional written variety.

Issues of politics, power, authenticity and acceptance remain prevalent regarding Irish Language standardization. A wide range of views and beliefs are still to be found in the Irish Language community; amongst speakers both within and outside the Gaeltacht. There are those who accept the authority of the standard language, and there or those who question its role and relevance.

The existence of an Caighdeán Oifigiúil some one hundred years after the foundation of the state in Ireland, and some 50 years on from the official grammar’s first iteration, shows us that standardization is a continuous process. It is not finite. In fact, some linguists would say that the only fully standardized language is a dead one!

Tá an Ghaeilge beo go fóill, áfach. The Irish Government have enacted legislation that provides for review of the Official Standard once every 10 years. As we approach the 10th anniversary of the most recent publication of the Caighdeán, perhaps we can expect another review before long?

To learn more, watch our recorded Ceardlann (Workshop) with Dr. Jonathan McGibbon, titled ‘Standardizing Irish: Discussing Dialectical Diversity‘.

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.