Super-Colonized Irish Syndrome

Ar chuala tú riamh faoi ‘Super-Colonized Irish Syndrome’?

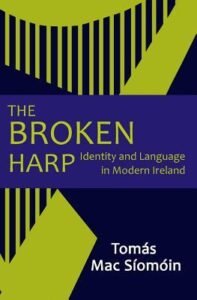

In “The Broken Harp: Identity and Language in Modern Ireland”, biologist Tomás MacSíomóin presents the decline of Irish as one of the most insidious outcomes of multi-faceted colonization from the 16th century through to the present day. He describes the residual effects of post-colonial trauma perpetuated, not only through intergenerational imitation of behavioural patterns, but also in the hereditary transmission of the colonial condition, via DNA structures and epigenetic profiles.

Although many of the traumatic episodes of Ireland’s past occurred generations ago, MacSíomóin contends that the past is not really ‘past’ since there is an ever-present hereditary factor in susceptibility to Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Thus, since the majority of Irish people have lived in conditions favouring PTSD for many centuries, and indeed, may still do in the north of Ireland, the entire populace of Ireland are heirs to what he terms, ‘Super-Colonized Irish Syndrome’. MacSíomóin also highlights the Sapir-Whorf Hypthosis, which maintains that the loss of a language entails the loss of a world-view tailored to the centuries of experience shared by those who spoke the language. Adopting the language of the colonizer exposes the colonized subject to a world-view in which he is a mere subaltern partner. As Bantu Steve Biko stated, “The most potent weapon in the hand of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed”. A potent weapon indeed.

The Kenyan Example

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is a celebrated Kenyan writer. He was already world-renowned when, around 1970, he renounced writing in English and instead committed to his native Gikuyu. He didn’t believe in writing in the colonizers’ language, and he wanted his work to be available to his own people, specifically to working class folk who did not know any English. Ngũgĩ famously highlighted the insane situation of the 1962 African writers conference, which excluded writers who wrote in African languages. A conference celebrating African writers, but not writers who wrote in their native tongue. The writers they were celebrating were writing mostly in English or French, the colonizers’ languages…

A Bilingual Nation?

All of this got me thinking about the language situation in Ireland. When we think of historic or modern ‘Irish literature’, we are usually thinking of literature written in English by Irish writers. But what constitutes Irish literature – is it literature written by Irish writers, is it literature based on Ireland, or is it literature written ‘as Gaeilge’? Ngugi is quoted as saying “It is the final triumph of a system of domination when the dominated start singing its virtues”. I believe most of our modern day negative attitudes towards the Irish language, and all things Irish, are echoes of our colonial past and the traumas that come with it.

It’s not to say we should stop writing in English, but why not hold the Irish language in as high regard as we do English? Why not aim for a bilingual nation? I always love reading out this quote from Conchúr Ó Socháin in 1930, a native speaker in Cork:

“Tá an Ghaeilge mar tine a bheadh éagtha ach go bhfanfadh sméaróid éigin ar fuid na luaithe ar an dtingéan, pén duine a mhairfeadh leis, go n-adófaí go mbeidh sí ina lán fuinnimh chomh lasmhar agus a bhí”.

“The Irish language is like a dying fire, but some embers still remain all over the ashes of the hearth. All it takes is for someone to rekindle the fire slowly but surely it will re-ignite, with flames as strong as it was before”.

Related Articles:

– An Gorta Mór and the Irish Language.

– Decolonize Your Hearts!

– The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis and ‘An Bata Scóir’.

– The Process of Decolonization.

Videos:

View Conchobhar Ruadh‘s previous workshops here.

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.