An Gorta Mór and the Irish Language

An Gorta Mór had a disastrous effect on Ireland and on the Irish language. The worst impact of this event, also referred to as ‘The Great Hunger’, ‘The Irish Famine’ or ‘The Potato Famine’, was felt in the poorest parts of Ireland, which was precisely where Irish remained strongest. By 1851, millions had either died or emigrated, and every Irish pub in the far corners of the globe probably owes its origins to the An Gorta Mór and the mass emigration of the Irish.

An Gorta Mór had a disastrous effect on Ireland and on the Irish language. The worst impact of this event, also referred to as ‘The Great Hunger’, ‘The Irish Famine’ or ‘The Potato Famine’, was felt in the poorest parts of Ireland, which was precisely where Irish remained strongest. By 1851, millions had either died or emigrated, and every Irish pub in the far corners of the globe probably owes its origins to the An Gorta Mór and the mass emigration of the Irish.

We see the shame and trauma associated with the language when we look at An Gorta Mór. Even before this tragic event, Irish was seen as the language of people with no prospects, but the 1840’s led to an even bleaker situation – an association of the Irish language with death and despair. For many people, it was a devastating decision to leave the only home they knew in search of a better future abroad. With the threat of starving to death, and their homes being forcibly taken from them, it’s no wonder that so many left behind their mother tongue too.

Delphi Lodge, Mayo

One tragic example of wanton suffering during An Gorta Mór concerns Delphi Lodge, in Co. Mayo. In March 1849, a large group of starving people in Louisburgh, Mayo, sought assistance from the relieving officer. He advised them to apply to the Board of Guardians meeting the next day at Delphi Lodge, ten miles away over the mountains. This was a hunting lodge owned by the Marquess of Sligo, a former governor of Jamaica. The starving tenants walked to Delphi Lodge through the night, but were informed when they arrived that the board were at lunch and could not be disturbed. When they finally did meet with them, the board denied them assistance, so they set out on the road home. Many of them perished over the two days. According to Robbie McVeigh and Bill Rolston:

“This one tragic episode cuts to the nexus of Ireland and colonialism. The truth of the empire was exposed in this moment. If the ‘greatest empire there ever was’ chose to make a people its subjects – against their will – then such an empire bore responsibility for their basic survival. There was no greatness or honour in starving to death under the imperial flag.”

In terms of the fallout from An Gorta Mór, it’s vital that we now honour, remember and connect with our ancestral heritage. Where we have come from can be just as important as where we find ourselves today. For most of my life, I would have been ignorant to the plight of emigration. Ancestry wasn’t at the forefront of my mind. My immediate family hasn’t any history of emigration, and I rolled my eyes every time I heard an American say they were 1/10th Irish. However, I get it now. It’s very important to acknowledge where our families have come from, and I accept anyone who has ancestry from Ireland or identifies as a Gael. Mourning is a vital part of decolonization, and mourning for our ancestors, mourning for what they lost and experienced is essential because for the majority of Irish who emigrated, they didn’t want to leave! They left because they had to! Death and despair were all that was left for them, and no wonder a lot of our songs and music are quite mournful and full of laments.

Famine Trauma

J. Lee and G. Moane, Irish psychologists, proposed in 1994, that centuries of English colonialism in Ireland relied on mechanisms of control, which included; physical coercion, sexual exploitation, economic exploitation, political exclusion, and control of ideology and culture. Specific traumatising experiences for the colonized Irish, according to these researchers, include systematic treatment as an ‘inferior race’ by the English, subjection to starvation(famine) while vast quantities of food were being exported, language and music censorship and educational oppression.

As such, it is entirely possible to suggest that Irish famine survivors may have, likewise, transmitted traumatically altered DNA to their offspring, provoking PTSD in the latter, and that the current Irish population still harbours such genes. Conditions favouring a marked incidence of PTSD, were abundant in Ireland in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, and in the northeast of Ulster during the last 30 years of the 20th century. Could a portion of the modern population of Ireland be suffering because of the traumatic effects of An Gorta Mór?

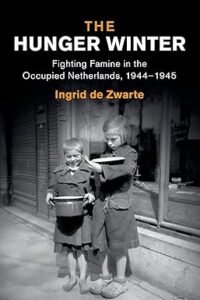

Findings from the Dutch famine in 1944 also strongly suggest the heritability of stress induced traits in human beings. Researchers found that the children of pregnant women exposed to famine were more susceptible to diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease and other health problems. Children of the women who were pregnant during the famine were smaller, as expected. However, surprisingly, when these children grew up and had children those children were also smaller than average. Subsequent research also found an increase incidence of schizophrenia in these children. Also increased among them were the rates of schizotypal personality and neurological defects.

Findings from the Dutch famine in 1944 also strongly suggest the heritability of stress induced traits in human beings. Researchers found that the children of pregnant women exposed to famine were more susceptible to diabetes, obesity, cardiovascular disease and other health problems. Children of the women who were pregnant during the famine were smaller, as expected. However, surprisingly, when these children grew up and had children those children were also smaller than average. Subsequent research also found an increase incidence of schizophrenia in these children. Also increased among them were the rates of schizotypal personality and neurological defects.

Tomás Mac Síomóin argues than that the health profile of Irish women exposed to An Gorta Mór and other Irish families, and hence of their descendants, can hardly have been very different from that of these Dutch famine victims. From this, I believe it’s not too much of a stretch to argue that many Irish people in Ireland and across the globe could be suffering from the effects of our ancestors trauma.

Notable Support from Abroad

There are some notable stories of goodwill amidst the bleak years of An Gorta Mór, particularly from those who observed the Irish plight from afar. I note that Drogheda FC carry the star and crescent of Turkey. Local historians trace the star and crescent back to 1210 when the British governor of Ireland, King John Lackland, granted the town its first charter. However, it is suggested that the club crest is also in reference and gratitude to a gift from the Turkish Sultan, who sent money and ships of foodstuff to the value of £10,000 during An Gorta Mór. This act of compassion only serves to show the inhumanity of the English Queen Victoria et al towards Irish suffering, as she donated a much lesser amount.

There are some notable stories of goodwill amidst the bleak years of An Gorta Mór, particularly from those who observed the Irish plight from afar. I note that Drogheda FC carry the star and crescent of Turkey. Local historians trace the star and crescent back to 1210 when the British governor of Ireland, King John Lackland, granted the town its first charter. However, it is suggested that the club crest is also in reference and gratitude to a gift from the Turkish Sultan, who sent money and ships of foodstuff to the value of £10,000 during An Gorta Mór. This act of compassion only serves to show the inhumanity of the English Queen Victoria et al towards Irish suffering, as she donated a much lesser amount.

Perhaps the most famous example of international solidarity during this period is the assistance of the Choctaw people in 1847. The Choctaws were the first tribe to be relocated during the Trail of Tears, starting in 1831, with thousands dying and many starving. When the Choctaw tribe heard about the plight of the Irish in the 1840s, they sent $170 to help the Irish people, which was then distributed by members of the Quaker community in Ireland. The gesture was never forgotten by the Irish people, and awareness of this historic gift increased even more so around the 150th anniversary of An Gorta Mór, in 1995. Perhaps this is why the ordeals of Native American tribes have long resonated in Ireland. President of Ireland, Mary Robinson, visited the Choctaws in Oklahoma in 1995 to express thanks for their historic gift, as did Taoiseach Leo Varadkar in 2018. 173 years later, the Irish people played a large part in raising over $8 million for the Navajo Nation and the Hopi Reservation affected by the pandemic.

Upcoming:

Turas Teanga workshop le Conchobhar Pádraig Ruadh, Jan 13th.

Related Articles:

– Decolonize Your Hearts!

– Super-Colonized Irish Syndrome.

– The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis and ‘An Bata Scóir’.

– The Process of Decolonization.

Videos:

View Conchobhar Ruadh‘s previous workshops in our Cartlann (Archive).

Join the online Irish community for cúrsaí, comhrá & ceardlanna, and follow along on social media @LetsLearnIrish – beidh fáilte romhat!