6 Reasons Why The Irish Language Declined

The reasons behind the historical decline of the Irish language are varied. Although this linguistic loss occurred relatively quickly in terms of the lifecycle of a language, Irish did not decline overnight. The 1851 census, the first one to include a language question, showed that less than 25% of people on the island spoke Irish. However, by the time An Gorta Mór (1845–48), occurred, various factors had already decreased the number of Irish speakers. The mass emigration that followed the potato blight only accentuated a process that had been started hundreds of years previously. Here are six of the most-cited reasons for the decline of the Irish language, in relatively chronological order.

1. The Tudors

Having survived the Norman invasions of the 12th century, the Irish language remained dominant on the island, thanks in part to being used by the native Gaelic ruling class. Although English was commonly spoken in urban bureaucracies, its use by landowning lords protected its prevalence. In the late 1500s, however, the English Crown sought to increase its control over Ireland. Ruled by the House of Tudor, an English royal dynasty of Welsh origin, the English pursued cultural hegemony as a means to a political advantage, forcing all landowners and politicians to speak English. Elizabeth I (1533–1603) was the last of these five monarchs of Tudor. As English author Sir John Davies stated, the Crown wanted to anglicise the Irish to the point that “there will be no difference or distinction, but the Irish Sea betwixt us.”

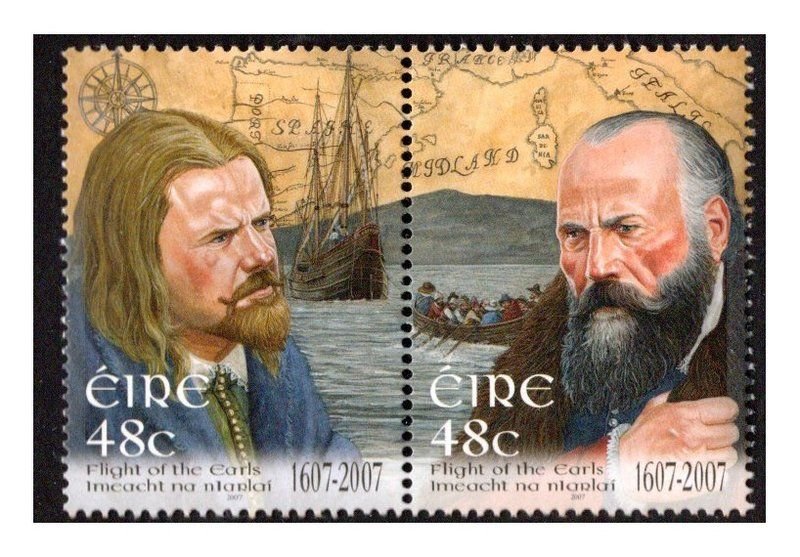

2. The Banishment of the Gaelic Rulers

Descendants of old Gaelic clans, the Ulster chiefs ruled the north and were the most influential native Irish leaders remaining. However, following defeat at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601, the chiefs were forced into exile in what was known as the Flight of the Earls. This occurrence officially ended the last significant bastion of native Irish political influence. The “Tudor conquest of Ireland” continued, looking to squelch Irish culture and its sources. Without a native ruling class, the Crown was more empowered to discourage the use of the Irish language.

Descendants of old Gaelic clans, the Ulster chiefs ruled the north and were the most influential native Irish leaders remaining. However, following defeat at the Battle of Kinsale in 1601, the chiefs were forced into exile in what was known as the Flight of the Earls. This occurrence officially ended the last significant bastion of native Irish political influence. The “Tudor conquest of Ireland” continued, looking to squelch Irish culture and its sources. Without a native ruling class, the Crown was more empowered to discourage the use of the Irish language.

3. The Penal Laws

While there were various decrees against Irish Catholics to tamp their freedoms (e.g. Statutes of Kilkenny in 1366), the Irish Penal Laws, particularly from 1695 onwards, made them official and widespread. Among other things, Irish Catholics could not possess weapons, enter higher paying professions such as law or medicine, practice Catholicism or use Irish in the legal system. By the time the last of the Penal Laws were repealed in 1829, the Irish language had been completely disassociated from any position of power. When Catholics were finally allowed to pursue higher offices and professions in Ireland, English had long been established as the language of influence.

4. The Establishment of National Schools

In 1831, the founding of the National School system further accelerated the decline of the Irish language. “Tally sticks”, referred to as “an bata scoir”, were used to beat children caught speaking Irish. School children were expected to wear this stick on a piece of string around their necks, and whenever they spoke in Irish, a notch was cut into the stick. Children were then punished according to the number of notches on their tally stick. This practice was said to have the support of many parents who saw the English language as necessary to their children’s future advancement.

5. An Gorta Mór

By the mid-19th century, most Irish speakers were found in the countryside, particularly among the rural poor. It was this demographic that suffered the most from the failure of the potato crop and the subsequent ‘Gorta Mór’, in the 1840s. It has been estimated that more than a million Irish died during the Great Hunger and another million emigrated, largely to the United States. Those affected most severely by a lack of food were not the English-speaking merchant or professional class, but the farmers and tradesmen who still had Irish as their native tongue. Within less than a decade, the number of Irish speakers declined significantly.

By the mid-19th century, most Irish speakers were found in the countryside, particularly among the rural poor. It was this demographic that suffered the most from the failure of the potato crop and the subsequent ‘Gorta Mór’, in the 1840s. It has been estimated that more than a million Irish died during the Great Hunger and another million emigrated, largely to the United States. Those affected most severely by a lack of food were not the English-speaking merchant or professional class, but the farmers and tradesmen who still had Irish as their native tongue. Within less than a decade, the number of Irish speakers declined significantly.

6. The Connotations of the Two Languages

As a result of all the above events, and perhaps already implied, the Irish language became less attractive to those looking for upward mobility. Encouraged by the Catholic Church, political leaders, and the Crown itself, English was necessary for political and economic advancement. Even the popular leader and reformist Daniel O’Connell considered the Irish language “backwards“. Having experienced generations of poverty and limited agency, many Irish saw the English language as a requirement to improve their station in life. It wasn’t until the Gaelic revival movement took hold in the late 19th century that these attitudes began to change.

The Good News!

While various political and economic factors led to the decline of the Irish language, the good news is that “an Ghaeilge” is on the rise again! Having survived several centuries of strife, now the number of Irish speakers grows every day. Thanks to the enthusiasm of learners at home and abroad, increased language resources and digital content, and continued government investment, the revival of Irish is still ongoing. Indeed, Irish is “now a far more popular subject of study throughout the diaspora than it was 25 years ago, a minority language that has an international presence“. The growth of Irish language learning outside of Ireland is an inspiring tale, and examples abound of learners and their motivations for attending Irish courses. There are many reasons for learning ‘an cúpla focal’, so why not join the Irish language community, and be part of this modern-day language revival!

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.