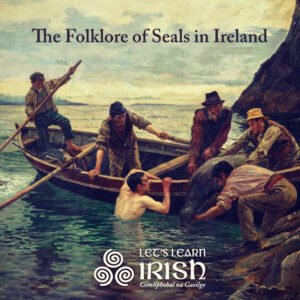

Na Rónta: The Folklore of Seals in Ireland

Being a coastal island, Ireland has developed a close relationship with seals throughout its history. Sometimes the bane of fishermen, sometimes a source of food and supplies in difficult times, and sometimes simply a creature to be admired, the species has always had a place in the imagination of the Irish people. In total, it’s not surprising that there is such a rich folklore concerning ‘na rónta’ (the seals) in Ireland.

Being a coastal island, Ireland has developed a close relationship with seals throughout its history. Sometimes the bane of fishermen, sometimes a source of food and supplies in difficult times, and sometimes simply a creature to be admired, the species has always had a place in the imagination of the Irish people. In total, it’s not surprising that there is such a rich folklore concerning ‘na rónta’ (the seals) in Ireland.

In fact, the breadth of stories involving seals prompted the Irish Folklore Commission to collect tales involving the creature within the Irish oral tradition, some of which are available online courtesy of University College Dublin (UCD). The stories, available in both Irish and in English, offer a unique insight into life and culture on the island in previous generations. The accounts were recorded by the Commission between 1935 and 1970, during the span of the Commission’s existence.

The Economic Importance of Seals in Ireland

Seals have been a protected species in Ireland since the 1976 Wildlife Act, but were sometimes hunted in the decades and centuries before that. Due to its waterproof qualities, its skin was used to make waistcoats and shoes, and the oil from its blubber sometimes fuelled lamps, cleaned sails, and even treated rheumatism and burns.

Seal meat was eaten, but generally only in times of scarcity. Remote areas like the Blasket Islands may have depended on the consumption of seal the most, being difficult places to survive (eventually abandoned in 1953). In the Blasket Islands it was reported that sometimes the oil from the seal was even used as “sauce” for potatoes.

Due to this dependence on seals, the water mammal featured in many stories passed among the local Irish populations. Some of them even included morality tales discouraging people from hunting them.

A Kinship with Humans

One reason that some of the stories collected by the National Folklore Commission often highlighted the bad luck brought about by hunting seals is that they were thought to have a close relationship with humans. Some stories suggest that seals are actually humans under enchantment, while others insist that some families, such as the Ó Conghaile or Ó Catháin, are descended from seals.

The folklore of seals in Ireland includes accounts of men about to kill a seal when the animal speaks and begs for mercy. The bewildered hunter always leaves the seal in peace and gives up harming them altogether. In another, a fisherman took a live baby seal home with the intent to use its skin for clothing the next day. In the middle of the night he awoke to hearing its mother call for it by its name. Finally, a seal hunter was stranded on a rock and about to be drowned, but was saved by a seal on the condition that he gave up hunting the species.

The Folklore of Seals in Ireland: The Selkies

First appearing in medieval texts, the selkie has been an important figure in Celtic tradition. According to legend, the selkie—normally in seal-form—can shed its skin and go to land as a human. Some sources suggest that this can only happen every seven years, while others proffer that it depends on the cycle of the moon. In order to return to the ocean, regardless, the selkie needs its skin.

The selkies, usually female, tend to be very attractive. Fishermen have the habit of falling in love with them. There are many stories in which a man steals a selkie’s skin and marries her. However, these stories seldom have happy endings, as the selkie longs for the sea and is typically unhappy. More times than not, she finds her skin and returns to the ocean, leaving behind a heartbroken fisherman.

The 2009 film Ondine gives a modern representation of a selkie story. In this romantic drama, Circus, played by Colin Farrell, finds a young woman in his fishing net and eventually falls in love with her, despite the trouble it brings.

The Work of the Irish Folklore Commission

The Irish folklore of seals has been recorded largely due to the efforts of the Irish Folklore Commission, which operated from 1935 to 1970, after which its function was taken over by the Department of Irish Folklore at University College, Dublin. Using the technology available at the time, the commission recorded oral stories from Irish citizens, many of which had been passed down for generations, and which included those told by famed storytellers such as Éamon a Búrc and Peig Sayers.

Because of the work of the Irish Folklore Commission and now the Irish Folklore Department at UCD, everyone can enjoy many of the seal stories that reveal an insight into Ireland’s past. If you’re interested in the folklore of seals in Ireland, you can find those bilingual stories here.

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.