Who was Peig Sayers?

Máire Ní Dhálaigh, from the Office of Public Works’s Blasket Centre, gave what is likely the most accurate and fair description of Peig Sayers: “Peig was the Netflix of her time.”

Máire Ní Dhálaigh, from the Office of Public Works’s Blasket Centre, gave what is likely the most accurate and fair description of Peig Sayers: “Peig was the Netflix of her time.”

Peig Sayers was born in 1873 in the townland of Vicarstown, Dunquin, located in the Gaeltacht of West Kerry. Her father was a respected patron of the oral tradition and passed on many of his stories to Peig, from Irish folklore to local history. Despite having to leave school at the age of twelve to work as a servant, Peig Sayers became one of the most famous storytellers in the Irish language.

Peig Sayers’s Life

Peig first hoped to move to America and join her friends and family there who had already become a part of the Irish diaspora. Her friend, Cáit Boland, had an “American wake” before travelling to the US and promised to send Peig the cost of passage to join her. However, Cáit later wrote to her that she had an accident and couldn’t pay for Peig’s travel. At nineteen, Peig married a fisherman and moved to the Great Blasket Island off the coast of County Kerry, a small isle that eventually became uninhabited in 1954. She had eleven children, but only six were still alive at the time of Peig’s passing.

In 1907, Robin Flower of the British Museum visited the Blaskets and was impressed by Peig’s stories. He was the first person to record her and present her tales to academia. Later, starting in 1938, Peig began to dictate her stories to Seosamh Ó Dálaigh from the Irish Folklore Commission. Although sources vary, it is believed that Peig told him between 350 and 432 different stories, which was enough to fill up over 5,000 pages of manuscript.

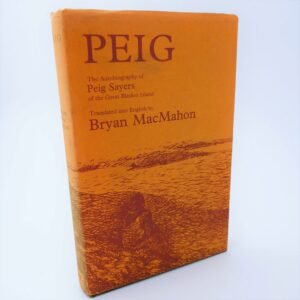

Peig, an Autobiography

Despite the immense catalogue of richly told tales that Flowers, and especially Ó Dálaigh, collected from Peig, there was one particular story that brought her to national attention: her own.

Despite the immense catalogue of richly told tales that Flowers, and especially Ó Dálaigh, collected from Peig, there was one particular story that brought her to national attention: her own.

Máire Ní Chinnéide, a Dublin teacher and regular visitor the Blasket Islands, convinced Peig Sayers to tell her autobiography to Peig’s son, Mícheál, for him to write down. Peig was illiterate in Irish and therefore had to dictate her life events to someone else. Mícheál sent the manuscript to Máire Ní Chinnéide, who edited it for publication in 1936.

Peig details, in Irish, her experience of growing up in poverty on the Gaeltacht island, as well as the Anglo-Irish politics of the era. Peig initially received significant praise and was part of the Irish national curriculum for secondary schools until the mid-nineties.

Peig Sayers also had her stories recorded in Machnamh Seanmhná (An Old Woman’s Reflections), which was published in 1939.

Controversy around the Autobiography

Peig is bleak in tone and composition, chronicling various tragedies in the life of Peig Sayers, from deaths in the family to bouts of starvation. Some criticized its inclusion on the Irish curriculum, suggesting that its dire subject matters became associated with the Irish language and made students less enthusiastic to learn Irish.

Peig is bleak in tone and composition, chronicling various tragedies in the life of Peig Sayers, from deaths in the family to bouts of starvation. Some criticized its inclusion on the Irish curriculum, suggesting that its dire subject matters became associated with the Irish language and made students less enthusiastic to learn Irish.

More recently, however, scholars and others familiar with the autobiography have pointed out that the content in Peig was heavily censured by Máire Ní Chinnéide. Peig Sayers, in fact, had a magnetic personality and many of her stories were said to be extremely funny. Much of the humor, however, was taken out to present a more homely, pious image thought to be more appropriate for school texts. Ní Chinnéide was later accused of making Peig Sayers conform to a more idealized version of the Irish peasant that was politically useful at that time rather than presenting an accurate reality of life on the island.

Peig Sayers and the Irish Language

The book Peig has often been associated with classrooms of bored teenagers, as well as excuses not to be interested in learning the Irish language. As Colm Ó Broin stated in The Irish Times, “It may be because Sayers just happens to share many of the characteristics that Irish people often came to associate with the language itself: she is poor, rural and old-fashioned. It’s rarely mentioned today, but for centuries many Irish people were ashamed of the language because it was spoken by the rural poor and not by the upper classes.”

In 2021, however, TG4 broadcaster Sinéad Ní Uallacháin spearheaded a documentary on Peig Sayers that helped demonstrated how much different Peig was than the person portrayed in the book. Instead, Peig Sayers had a strong sense of humor and was a born performer. Ní Uallacháin, among others, have taken up the effort to give a more accurate image of one of Ireland’s most important storytellers and the valuable role she played within Irish culture. It explores how Peig became synonymous with Irish, as well as Ireland’s complicated past with the language.

Others have recently contributed to the defense of Peig. Sorcha de Brún, from the University of Limerick, suggests that the book deserves a place among other world literature, being in dialogue with women’s experiences in other locations and historical periods. She takes that many of the issues addressed are relevant to young people today, including “having one’s own home, work, leaving home, and the sustaining power of friendships.”

Although Peig Sayers has been gone for a long time know, it appears that she is coming back into vogue. And, it’s credit well given, as much of Ireland’s oral tradition has been preserved thanks to her work.

Bígí páirteach!

Join the online Irish community at LetsLearnIrish.com.

Follow on social media @LetsLearnIrish.