A Brief History of the Irish Language

“Not to learn Irish is to miss the opportunity of understanding what life in this country has meant and could mean in a better future.” – Seamus Heaney.

Dating an ancient language is one of the toughest challenges a scholar can take on. It is a complex process that involves linguistics, geography, history, archaeology and genetics, as well as the study of other cultures that may have a similar language to the one being researched. Regarding the history of the Irish langauge, as with many other members of the wide Indo-European Language Family, this endeavour is full of possibilities, what ifs, and contradictions…

Primitive Irish and Ogham Stones

One of the most certain possibilities is that the oldest form of Irish we know, Primitive Irish, (also known as Archaic Irish or Proto-Goidelic) was introduced or developed in Ireland as late as the Iron Age (the pre-Christian Gaelic period). If this is true, then for 40% of the time that Ireland has been inhabited, nobody spoke anything similar to the Irish language, as the Bronze Age, Neolithic and Mesolithic cultures before the Gaels couldn’t have spoken it.

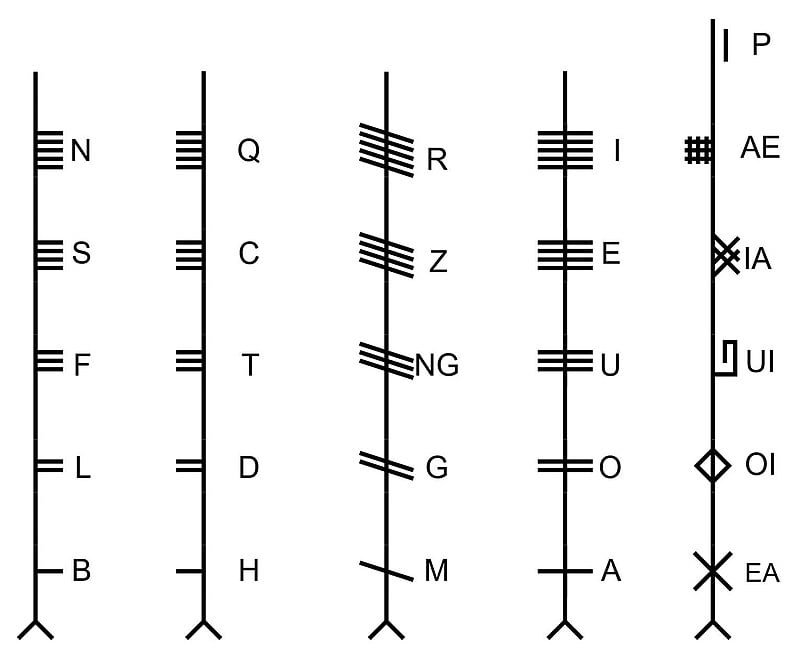

Our oldest script in the history of the Irish language comes from Ogham stones, which were erected anywhere around the 2nd to 5th centuries AD. They are usually memorials, and carry inscriptions in Primitive Irish and Latin, carved using a possibly indigenous alphabet called Ogham. The inscriptions are often done in Latin also, so from the get go, our native written evidence for Irish links it with the language of learning that Christianity brought to Ireland in the 5th century.

Irish Christianity brought also literary production and book-making technologies. About 200 years after its coming to Ireland, the Irish were suddenly producing a flourishing culture of written records, not only tales and legends but also genealogies, chronicles, annals, medical books, religious books and much more, in a mix of Latin and the first evolution of Irish, from Primitive Irish to Old Irish.

Old Irish and Latin were to be the languages of Irish scholarship for the next 200 years.

Middle Irish

By the 900s, after a century of social upheaval due to the coming of the Vikings, Old Irish had evolved into Middle Irish, and it became instead the standard language of scholarly learning. It is very remarkable that the Vikings gave Ireland its first settlements which would grow to become the modern Irish cities: they were absorbed into Irish society in terms of customs, religion, naming and, of course, language. What was it about the Irish language that made it so impervious to foreign influence?

Same thing happened when the Normans came later. It was less of an ‘invasion’ and more of a ‘joining the party’, as Norman lords became, extremely quickly, fully involved in native customs and language just like the Vikings had. The difference was that the King of England’s eyes were on them, but when they weren’t, the new Norman-Irish lords of Ireland remained essentially Gaelic.

Early Modern Irish

Early Modern Irish is associated with the 13th to 18th century. Around this period, the King’s authority in Ireland was not much more than nominal. The Statutes of Kilkenny in 1366 failed to prohibit the use of Gaelic language and culture, and it wasn’t until the reigns of Henry Tudor and Elizabeth I that a full-scale conquest of Ireland was enacted. As more and more native and Norman-Irish chieftains submitted to the Crown, the rest were busy fighting each other as the Gaelic system crumbled. The last bastions of Gaelic power were destroyed during Oliver Cromwell’s campaign of racial and cultural genocide in the mid 1600’s, after which all of Ireland was left in the hands of an English-speaking Protestant aristocracy and the surviving Catholic population was reduced to poverty and servitude.

This Anglo-Irish aristocracy ruled the country, but it was the native Irish who worked their farms. As Ireland itself developed institutions and government administration in English, it led to Irish parents making the heart-breaking decision of not passing Irish onto their children, as without English social advancement would be impossible. A National Schools system emerged in 1830. Exclusively English-speaking, kids who spoke Irish were beaten with a stick. 20 years later, millions of native Irish speakers died or were forced to emigrate due to An Gorta Mór. Irish went from being the predominant language around 1700 to being the language of only 25% of the population by 1850, and only about 5% by 1900.

A Cultural Revival

Interestingly, it was the descendants of that same Anglo-Irish aristocracy who launched a life-changing cultural recuperation of the Gaelic past in the turn to the 20th century. Led by antiquarians, intellectuals, artists, scholars and writers (most of the Protestant Anglo-Irish), a cultural revolution began where the descendants of the Colonists, just as everywhere else, asked themselves a fundamental question: are we from here or are we from there?

Suddenly, the heroes and gods of Irish legend were everywhere: theatre plays, poetry, spiritual speculation, re-tellings of the old stories. The Gaelic League was founded, and the contents of medieval Irish manuscripts translated for the first time. In politics, the archetype of Erin, the Goddess of Sovereignty, became the symbol of the path towards the Rising of 1916. For the first time in hundreds of years, Ireland was again being inspired by its old traditions.

And through all this, it is simply incredible that the language survived at all. After being resuscitated in the early 20th century, it still had a long, bumpy road to go before it could be thought of as ‘back’. The government of the newly-founded Irish Republic failed to properly support Irish, or foster sufficient motivation for its learning among the general population. In school, it became a source of annoyance and stress, and as any foreigner as myself can attest, shame about speaking or not speaking it still pervades conversations about the language.

The Irish Language Today

But today, about 100 years after the creation of the Republic, I think we can say that Irish is definitely ‘back’. In and outside of Ireland, a community of people with love for this island is changing things. Gaelic-speaking schools are thriving. There’s hundred of Irish courses, in-person events, theatre plays, social media accounts and all sorts of art being created in Irish; and it has become ridiculously easy, in a ridiculously short amount of time, to find ways to expose oneself to it. If you’re considering taking an Irish class, check out these 4 less obvious reasons to learn Irish!

Understanding the history of the Irish language is important because it is a story without an end. And all of you are choosing to become a crucial part of it. As a foreigner who studies this it feels as history itself unravelling before my eyes, right here, right now. And perhaps in 100 or 250 years, an Irish speaking population in Ireland may remember that time they almost lost their language for good, and how they got it back by opening it up to the world.

Santiago Rial is an Argentinian-born independent researcher of Irish history, mythology, heritage and language.

You can view Santiago’s presentation, titled ‘A Brief History of the Irish Language’, by visiting our Cartlann (Archive).

Join the online Irish community for cúrsaí, comhrá & ceardlanna, and follow along on social media @LetsLearnIrish – beidh fáilte romhat!